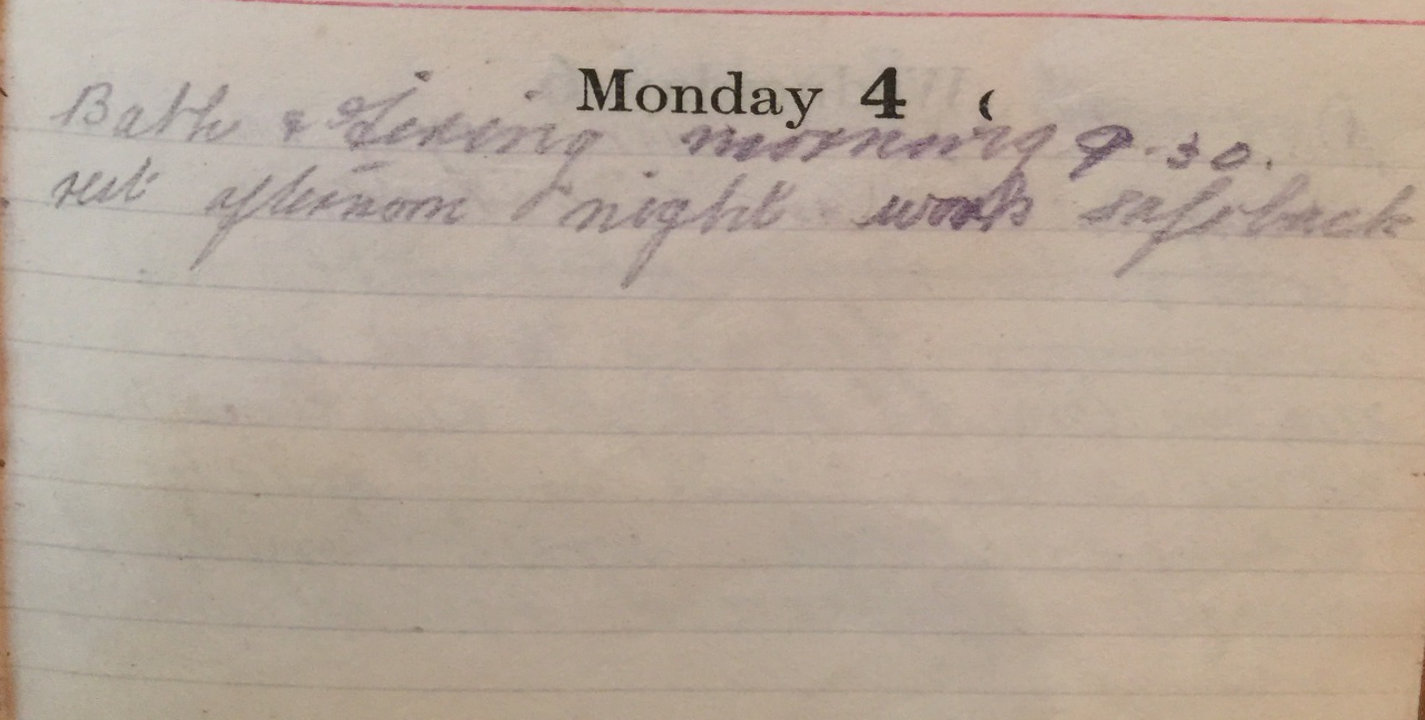

Monday February 4th, 1918

Bath and Firing morning 9:30. Rest afternoon. Night work – safe back.

Firing Range

Frank went to the firing range again this morning. Marksmanship was a valued skill before and throughout the War. In 1914, the regular British Army was recognized to comprise crack shots. Indeed if more than half of an infantry brigade weren’t certified as marksmen – the big brass was not pleased. Even more of an incentive, and dependent upon the level of marksmanship attained, it could also make a big difference to a soldier’s pay. The German forces mistook rapid firing from the SMLE rifles as machine gun fire in the early months of the war (a fact that was subsequently used in an advertising campaign by Lee-Enfield). This skill with the rifle possibly contributed to the British Army’s complacency in the face of modern weaponry as each Battalion only had two machine guns at the outbreak of war.

Considerable care had been taken to find a suitable firing range for B and D Companies in the foothills behind Vladaja. The official publication ‘Musketry Regulations’¹ provided comprehensive instructions for selecting such sites and setting up effective firing ranges. It also specified the contents of firing drills and field exercises.

Frank doesn’t include details of his firing accuracy today, unlike his entry of January 26th. Perhaps it was nothing to write home about.

Snipers in WWI

The British Army was not equipped to evade or to retaliate to enemy sniper fire at the beginning of the war. As Major E. Penberthy, former Commandant of the Third Army Sniping School, noted: ‘In the early days of the war, when reports of German ‘sniping’ began to be published, it was commonly considered a ‘dirty’ method of fighting and as not ‘playing the game’.’²

The casualties of this type of warfare included Brigadier General R.C Maclachlan (a brother of Lt. Col AFC Maclachlan, former commander of the 13th Manchester). ‘On 11th August 1917 whilst visiting the trenches under his charge he was shot at and killed instantly by a German sniper.’†

It took until mid-1915 for the British Army to respond in kind, but by late 1917 it was dominant.³ Not only was sniping taught as a discipline, but elephant guns were brought to the front to pierce the iron sheets behind which some German snipers hid. British snipers themselves used various camouflage tactics including ‘ghillie nets’ (originally used by Scottish gamekeepers (ghillies) to sneak up on poachers). This photograph shows the back of a canvas and steel tree observation post in May 1915. Such structures were also use by snipers.

The best sniper in the war with 378 ‘kills’ and over 300 captured enemies was Francis Pegahmagabow, an Ojibwa, with the Canadian Army.

13th (Service) Battalion War Diary – 4th February 1918 – Vladaja Camp

GRO number 302 para 1691 was published. Extract and additions:- The personal Mess Allowance issued to an Officer will be paid by him into the Mess Funds of his unit or that to which he is attached. Following OR struck off under GRO 1011 as follows:- 3 with effect from 2-2-18, 2 from 3-2-18 and 4 from 4-2-18.

References & Further Reading

Great War Centenary Article by John Lewis-Stempel in The Express June 22, 2014

¹ Musketry Regulations Part I of 1909 and Part II Rifle Ranges and Musketry Appliances of 1910

² British Snipers in the WWI trenches in OldMagazineArticles.com

³ Martin Pegler, writer of ‘Sniping in the Great War‘, interviewed in The Sun, March 23rd, 2017

† 1917 Rifle Brigade Chronicle, post thread on Maclachlan brothers on Great War Forum

Francis Pegahmagabow in Wikipedia

Camouflaged observation post, copyright IWM