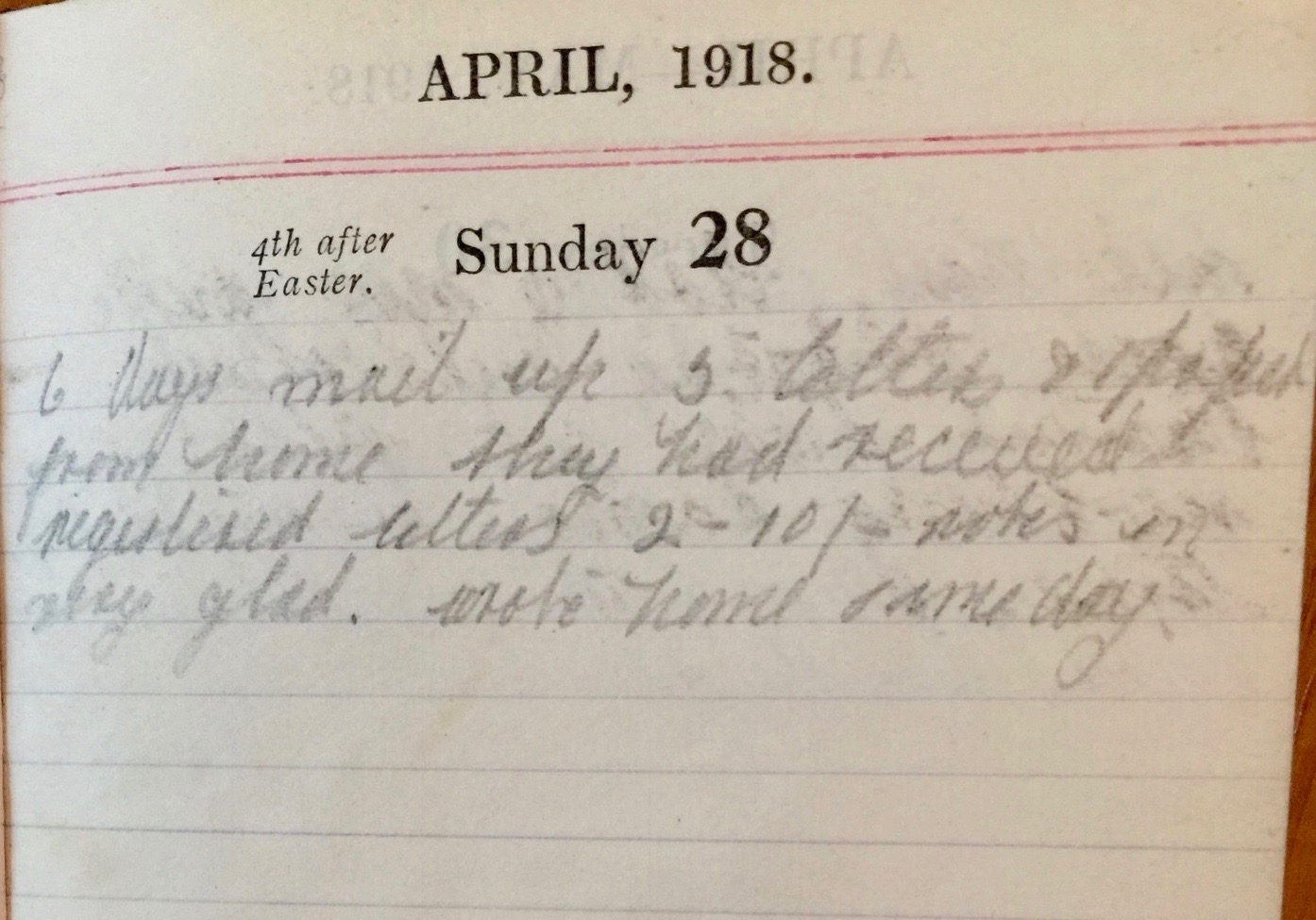

Sunday April 28th, 1918

Six days mail up five letters and paper from home. They had received registered letters with two 10 shilling notes in. Very glad. Wrote home same day.

Communication

Frank gets a pile of letters today and a newspaper, and then writes back immediately. Exchanges of this sort are critical for morale both at home and abroad and the authorities know it. However, the authorities also recognize that unfettered communication can be dangerous to the war effort and, since 1914, have been determined to control it.

As soon as war was declared, the British cut all the subsea cable links between Germany and the USA and between Germany and Britain. They also introduced censorship of all written correspondence and prohibited aliens from owning such things as carrier pigeons and radio transmitters. The freedom of the press was also controlled under the provisions of ‘The Defence of the Realm Act’ of August 1914 and its subsequent iterations.

Propaganda

Also in 1914, to control the content further, the government secretly established a War Propaganda Bureau (WPB). Famous figures involved in its output, included writers like John Buchan, Sir Arthur Conan-Doyle and HG Wells, and artists, such as Paul Nash and Francis Dodd.

Propaganda, as defined by Sir Campbell Stuart at the beginning of his book, is ‘the presentation of a case in such a way that others may be influenced’.¹ It was used at home and abroad with both fighting forces and civilians. For example, the British whipped up the plight of ‘poor Belgium’ to validate the war and encourage recruits.

While propaganda has existed for centuries, most consider WWI as the start of modern psychological operations in support of a war effort. This was largely due to the availability of modern distribution channels including radio, film and aeroplanes. Some campaigns spectacularly backfired, such as the German production of a medal commemorating its triumphant sinking of the Luisitania. Others worked too well, with the sometime excesses of the British campaign leading to scepticism about its ‘official information’ in the post-war period.³

Artists at War

Being employed by the WPB did not mean that the artists and writers were mindless pawns. Paul Nash became a official war artist in September 1917, after having been injured while serving on the Western Front earlier that year. He went back to the front as a war artist, covering both the end of the Third Battle of Ypres and the Canadian troops in Vimy. What he saw transformed him, and his paintings are some of the most searing indictments of WWI. As he wrote to his wife in November 1917:

‘I have seen the most frightful nightmare of a country more conceived by Dante or Poe than by nature, unspeakable, utterly indescribable. In the fifteen drawings I have made I may give you some idea of its horror, but only being in it and of it can ever make you sensible of its dreadful nature and of what our men in France have to face…

Evil and the incarnate fiend alone can be master of this war, and no glimmer of God’s hand is seen anywhere. Sunset and sunrise are blasphemous, they are mockeries to man, only the black rain out of the bruised and swollen clouds all through the bitter black night is fit atmosphere in such a land. The rain drives on, the stinking mud becomes more evilly yellow, the shell holes fill up with green-white water, the roads and tracks are covered in inches of slime, the black dying trees ooze and sweat and the shells never cease….

It is unspeakable, godless, hopeless. I am no longer an artist interested and curious, I am a messenger who will bring back word from the men who are fighting to those who want the war to go on for ever. Feeble, inarticulate, will be my message, but it will have a bitter truth, and may it burn their lousy souls.’

Nash remained an official war artist until after the War had ended and, through his work, had a significant impact upon how it was remembered.

British Propaganda by 1918

Over the course of the war, the British approach to propaganda evolved and by February 1918 there were three distinct units:

Set up in mid-1917, the cross-party National War Aims Committee was responsible for delivering patriotic information across Britain.

The War Propaganda Bureau had been replaced by the Department of Information in 1917 and then subsumed within Lord Beaverbrook’s Ministry of Information in February 1918. This unit focused upon civilian propaganda in Allied and neutral countries.² These efforts included the British weekly publication ‘Courrier de l’Air’ delivered to territories occupied by the Central Powers in France and Belgium.

Also in February 1918, Lord Northcliffe became Director of Propaganda in Enemy Countries – mainly focused upon Austria Hungary and Germany (the latter briefly under the control of HG Wells). Lord Northcliffe’s operation, based at Crewe House, is the subject of Sir Campbell Stuart’s book.¹

13th (Service) Battalion War Diary – 28h April 1918 – Crow Hill

Our artillery was especially active on the Pip Ridge and in the region of Ouvrage and Trapeze de Stojakovo. Enemy retaliated on P4.5, P5 and Horse Shoe also Whaleback.

At 21:20 hrs 3 green lights at 10 minute interval were fired in easterly direction from Flat Iron Hill, there was no apparent result. The Bulgar has been know to use these lights as a signal that he is sending out a patrol or for the return of one. Our patrols were in that neighbourhood at this time and saw no signs of any enemy movement.

A patrol to Goldies IV found proclamations in matchboxes, they had left out on a previous patrol untouched. There are five sangars in all on N shore of Goldies. Only two of the proclamations left previously by the sangars were found. A patrol to Daugli Village found no trace of the proclamation they had left on the isolated house on NW of village, they posted a few more. Our artillery bombarded the Crete des Tentes all night. It was noticed on three occasions, white ground flares were followed by long bursts of machine gun fire. Visibility was high.

Operation Order No 36 issued (App No 6). The battalion will be relieved by the 9th South Lancs Reg on the night of 1st / 2nd May 1918.

References & Further Reading

¹ ‘The Secrets of Crewe House‘ by Sir Campbell Stuart KBE, 1920

² ‘Propaganda 1914-1918‘ from the National Archives

³ ‘Allied Psyop of WWI‘ by SGM Herbert A Friedman (retired) on Psywarrior.com

* (Art.IWM ART 2705) work by Paul Nash, copyright of Imperial War Museums

One thought on “Propaganda – April 28th, 1918”

Comments are closed.