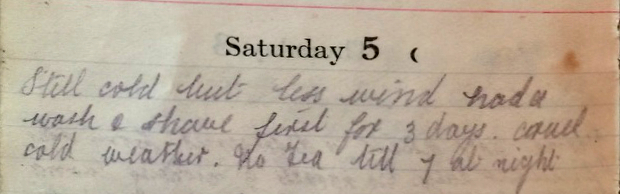

Saturday, Jan 5th, 1918

Still cold but less wind. Had a wash and a shave, first for three days. Cruel cold weather. No tea until 7 at night.

Hygiene

Frank seems a bit happier today. It was probably because, despite the continued poor weather, he has his first wash and shave for three days. Personal hygiene and tidiness were important to the morale of the troops. They were also key building blocks for good sanitation in the armed forces.

Others included camp design (eg the positioning of latrines), water and food hygiene, vaccinations, preventative drugs, protective clothing and the overall supervision and care of the troops by their superior officers. This photograph shows an officer inspecting the feet of his men, checking for trench foot and other diseases.

Sanitation & the Army

Long before WWI it was recognized that casualties from ill health could be more significant than those from the battlefield. As such, a sick army could compromise the outcome of a battle and even a war.

As was noted in a lecture during WWI on sanitation and hygiene: ‘In the various British campaigns between the time of the Crimea and the South African War of 1899-1902, the losses in our forces from disease bore the proportion of nineteen cases to one of wounds by the enemy. During the South African War the average force during the two years was 208,000 men. The admissions to hospital during that period were approximately 404,000, of which no less than 380,000 were cases of disease…..We have profited by experience, and to-day every effort is made, not only to prevent disease, but to educate the soldier to appreciate the risks, and by instruction to teach him how to avoid or nullify them.’¹

It is interesting and sad to note that the ratio of casualties of 19:1 as mentioned in this quote roughly correspond to those of the British Salonika Force 1915-1918.

Personal Grooming

In amongst the Tommy’s 60lb kit was the ‘holdall’. It was a cotton or canvas roll designed to hold what the Army called ‘necessaries’. They comprised (left to right) spare boot laces, a button brass (to allow the soldier to clean tarnished buttons without marking his uniform), a toothbrush, comb, shaving brush and a cut throat razor. To keep them safe from pilfering or loss, the soldier was supposed to mark the items with the last four digits of his regimental number.

The knife, fork and spoon were officially carried separately in the haversack though unofficially soldiers often seemed to carry them in their holdall. The soldiers often identified the spoon as the most important item and the knife as the least useful. Some soldiers sharpened one side of the spoon to help it serve as a multi-functional eating implement.

The third photograph in this series is of a “housewife” pronounced “hussif”. It was designed to hold spare buttons, needles and thread. This example belonged to a soldier in the 3rd battalion of the Royal Sussex Regiment. All the items in these images are genuine WWI artefacts.

References & further reading

* images and information courtesy of Wainfleet, a member of the Great War Forum.

^ image copyright belongs to Imperial War Museums

¹ extract from a lecture on Sanitation and Hygiene from the book, “Military Organisation and Administration” published by Major G. R. N. Collins, 4th. Battn. Canadians Instructor, Canadian Military School, in 1918. Medical Front WWI

‘How to keep clean and healthy in the trenches‘ by Imperial War Museums

One thought on “Hygiene – January 5th, 1918”

Comments are closed.