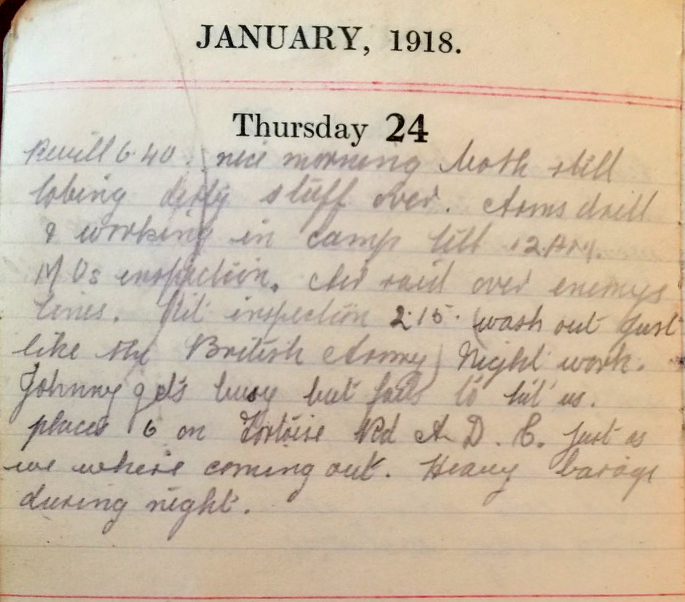

Thursday Jan 24th, 1918

Reveille 6:40. Nice morning. Both still lobbing dirty stuff over. Arms drill and working in camp until 12. MOs inspection. Air raid over enemy’s lines. Kit inspection 2:15 (wash out just like the British Army). Night work. Johnny gets busy but fails to hit us. Places six on Tortoise Road ADC just as we were coming out. Heavy barrage during night.

Camps

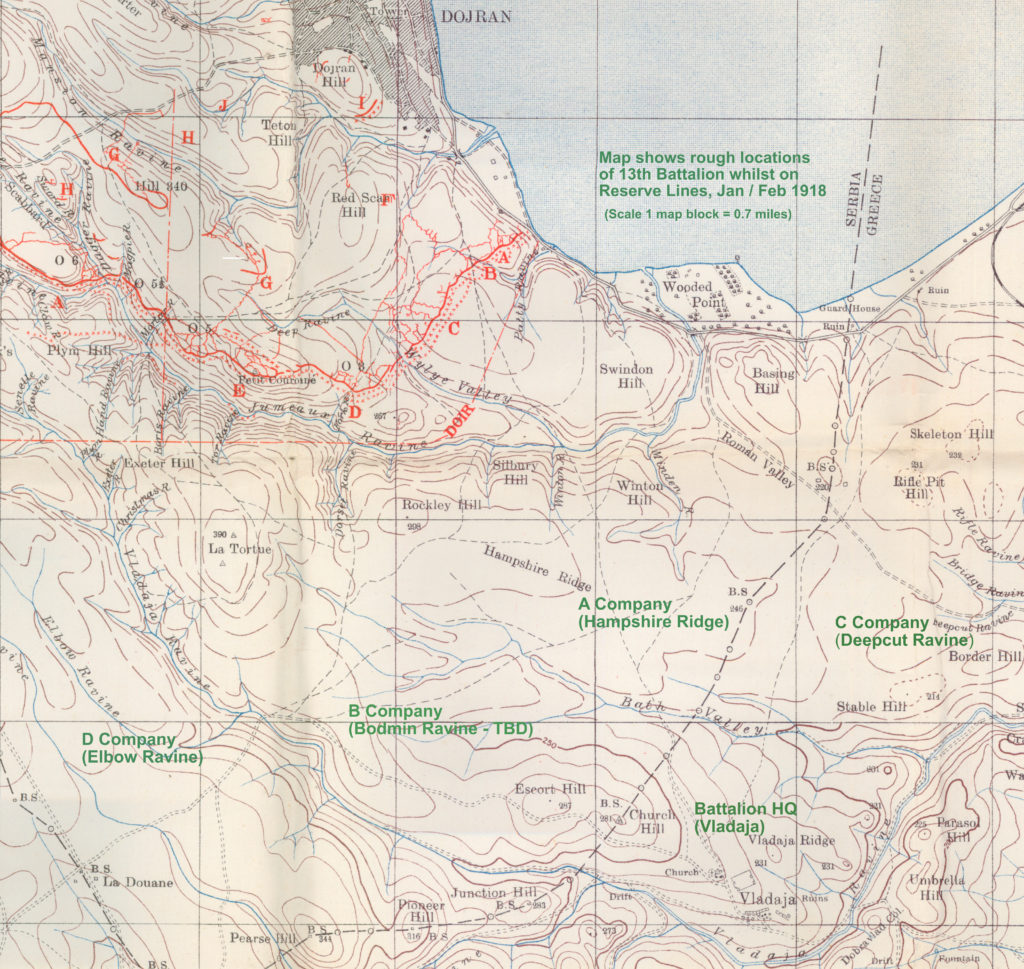

Whilst on the Reserve lines, the troops are clearly still in the line of fire. Almost daily, both Frank and the Battalion report a variety of near-miss and occasional on-target bombardments. The map shows the location of the camps in which the 13th are stationed. Unfortunately we cannot find Frank’s Bodmin Ravine. Each block on the map is approximately 0.7 miles, therefore the troop are within three miles of the enemy’s front line (marked in red ink). Larger artillery had a range of several miles (eg the range of the British 18 pound, Mark III howitzer was over six miles) and deployed indirect fire (ie the projectile lobbed into the air in a sort of arc). Enemy artillery typically had even greater range. An extreme example is the German’s notorious Paris Gun that had a range of over 80 miles!

Dugouts

With the very real danger of artillery fire, Frank is no longer under canvas but is now assigned to dugout number 21 at Bodmin Camp. Dugouts were used extensively throughout WWI in many theatres of war.

AA Milne, the author and creator of Winnie the Pooh, served with the Royal Corps of Signals. He described an evening in a dugout during WWI, “We sat there completely isolated. The depth of the dugout deadened the noise of the guns, so that a shell-burst was no longer the noise of a giant plumber throwing down his tools, but only a persistent thud, which set the candles dancing and then, as if by an afterthought, blotted them out. From time to time I lit them again, wondering what I should be doing, wondering what signalling officers did on these occasions. Nervously I said to the Colonel, feeling that the isolation was all my fault, `Should I try to get a line out?’ and to my intense relief he said, “Don’t be a bloody fool.”¹

Dugouts ranged in size from those able to hold a handful of men to a whole Battalion. Sometimes they were very deep underground, though this was impossible with the rocky terrain of the Dojran front. This photograph shows the 9th Battalion of the King’s Own Royal Lancasters in 1918. The crosses on the horizon to the right of the photograph show the Medical Officer’s dressing station – also built into the hillside.

13th (Service) Battalion War Diary – 24th January 1918 – Vladaja Camp

At about 04:00 hrs our artillery commenced a heavy bombardment which caused considerable retaliation. Many rounds fell around the battery and near Battalion HQ but no damage was done. The bombardment lasted about one hour. About 08:30 hrs the enemy shelled the Rockley region fairly heavily after which the day was mostly quiet. The baths at Bath Valley are allowed to the Battalion on the 25th. 1 OR struck off effective strength under GRO 1011 from 21-12-17. 7 OR having rejoined are taken on from 23-1-18. 1 OR having joined is taken on from 23-1-18.

References & further reading

^Dojran Map, Edition 3A, June 1917. McMaster University, Ontario, Canada (see entry of 23 Jan 1918 for link)

* photograph from collection of Sir Thomas Harley who served with the 9th in Salonika. From King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment Museum website. Image may be subject to copyright.

¹ ‘It’s too late now: the Autobiography of a Writer’, AA Milne, Pan-MacMillan, Sept 2017