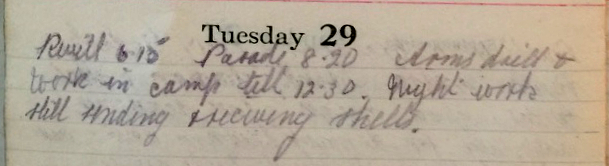

Tuesday Jan 29th, 1918

Reveille 6:15, Parade 8:20. Arms drill and work in camp till 12:30. Night work. Still sending and receiving shells.

The War on Malaria

Today Frank reports continued skirmishes between the Allied and enemy forces. However combat wasn’t the only, or even the main, danger facing the troops of either side.

Malaria was the unexpected adversary for all the armies fighting in Macedonia and proved to be most challenging. Each army deployed slightly different tactics to fight the epidemic. Their results varied.

Quinine was used across all armies though there was considerable debate about whether it should be used as a prophylactic or only as a treatment once infected.

Mosquito nets of all descriptions were used – on beds, tents, hats etc. Unfortunately for the BSF, these nets were usually in short supply and difficult to replace if damaged. CM Wenyon et al posited that it would have been best if all available money and resources had focused solely on good netting.

Significant efforts were also made to eradicate the mosquitoes’ breeding grounds. This photograph shows men of a Highland battalion digging a channel to drain the Daubratali Marshes in Macedonia.* Such work also met with mixed success. The British occupied an area of 2000 square miles, yet many of their anti-malaria prevention strategies encompassed a one-mile circumference around each camp. The fact that mosquitoes can fly many miles was unknown at the time.²

The British force seems to have the highest incidence of malaria (37% of the troops were infected between 1916 and 1918) but, at 0.7%, the lowest fatality rate. The French infection rate was lower but the death rate was much higher at 6.4%. The data for the Central Powers is less reliable, but their fatality rate was reportedly about 4%.¹

Moving the Problem?

The recurrent nature of malaria combined with the U-boat threat (which inhibited overseas evacuation, particularly in early & mid-1917) placed a heavy demand on the medical services. Consequently, at its height, almost 50,000 beds were needed for hospital and convalescent patients of the BSF. This equated to one third of the total strength of the force. Macpherson & Mitchell noted that this ‘… had no parallel in other theatres of war’.³

Later in 1917/18, under the Y-scheme, Britain would evacuate thousands of heavily infected cases – many to convalesce in the UK. This was useful as it disrupted the cycle of infection between man and mosquito.

However moving troops between theatres of war could also create problems. When three Battalions from the 65th and 66th Infantry Brigade are moved from Salonika to France in June 1918, many have malaria. Indeed, the 13th Manchester, 14th King’s Liverpool and 12th Lancaster Fusiliers are each reported as having 75-80% infection rate amongst their men. Sometimes such troop movements led to outbreaks in traditionally malaria-free areas of the world, including the Kent coast.

13th (Service) Battalion War Diary – 29th January 1918 – Vladaja Camp

Instructions re Claims for War Pay are issued. 6 OR (Chronic malaria cases) are struck off the effective strength with effect from 8-1-18. 5 OR are compulsorily transferred from the AOC and posted to this Battalion with effect 24-1-18.

References & further reading

¹ ‘Malaria’s contribution to WWI – the unexpected adversary‘ by Bernard J Brabin, in the Malaria Journal

² Malaria in Macedonia 1915-19 by Wenyon CM, Anderson AG, Mclay K, Hele TS, Waterston J., RAMC, 1921. Precis in Google Scholar.

³ ‘Medical Services General History Vol IV‘ by Major General Sir WG Macpherson & Major TJ Mitchell, HMSO, 1924 from IWM

* Draining the Daubraltali Marshes, Macedonia from IWM

One thought on “Skirmishes & Malaria – January 29th, 1918”

Comments are closed.