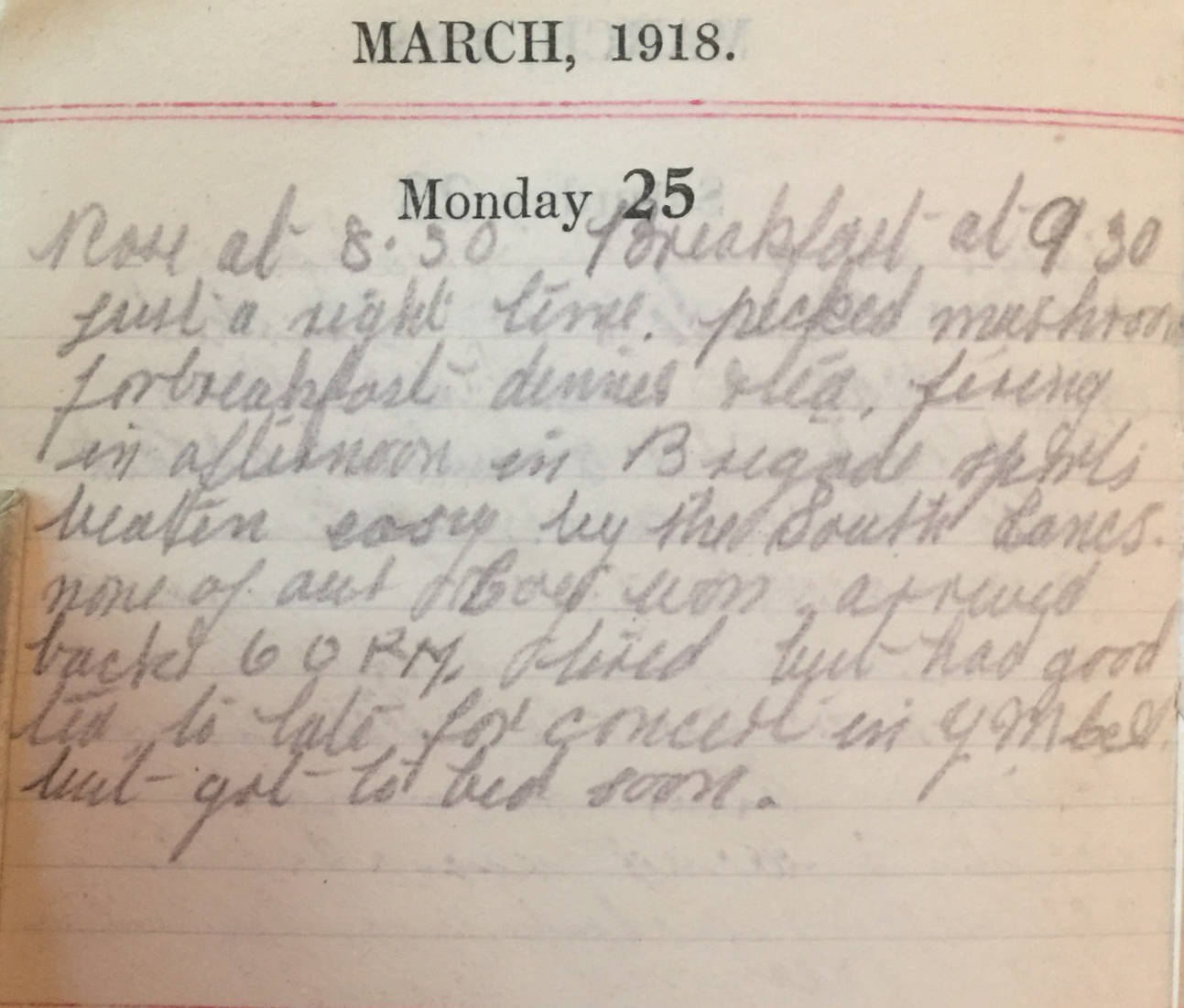

Monday March 25th, 1918

Rose at 8:30. Breakfast at 9:30. Just a right time, picked mushrooms for breakfast, dinner & tea. Firing in afternoon in Brigade sports. Beaten easy by the South Lancs. None of our Company won. Arrived back 6pm, tired but had a good tea. Too late for concert in YMCA but got to bed soon.

Mushrooms & Firing

Frank hasn’t said much about food recently, but is obviously delighted by his haul of mushrooms today. He is in Rates for the Brigade sports. Unfortunately B Company was ‘beaten easy’ by South Lancs and failed to win in any of the competitions. He is to remain in Rates overnight, but is too late leaving the sports day to make it to the YMCA concert.

Frank and the other participants have missed out on the ‘open warfare’ exercise conducted by the the Battalion back in Olasli.

Looking up ‘open warfare’, the only reference I could find to it in WWI related to the US Army. Each US Army Division was ~28,000 troops – double the size of those in the British Army. ‘In order to help this unorthodox organization, Pershing and his key staff officers at General Headquarters (GHQ) promulgated what was by 1917 a rather unique, though somewhat ill-defined, combat doctrine. Commonly called “open warfare,” official AEF doctrine was based on prewar US Army regulations, and stressed maneuver and marksmanship over frontal attacks and firepower. At its best, when used by experienced troops and supported by massive amounts of artillery, “open warfare” shared some similarities with the infiltration tactics used by German storm-troopers. At its worst, when inexperienced officers took it at face value and attempted attacks with unproven, poorly trained, and weakly supported lines of “self-reliant infantry,” it led to horrific casualties.¹

Update on the Spring Offensive

Meanwhile, the ‘open warfare’ tactics of the German Spring Offensive were yielding strong results for the enemy.

The tone of The Guardian’s reporting has changed (and bear in mind that the Defence of the Realm Act ensured that reports were censored). Under the heading, ‘The Battle in France’: ‘We have suffered a severe defeat in France, but so have all the other armies that have fought there in this war, and each in turn has known how to draw victory from defeat. What other armies have done – we say it in no spirit of boastfulness – the British army can do too.’²

Over 1 million artillery shells had been fired within the first five hours of the attack, which was across a front of 50 miles.° Commenting on these tactics, the report continues, ‘…whereas we in our offensive had attacked on a narrow front in order to reduce the scale of casualties and also to lengthen our endurance, the German principle apparently was that to draw out the battle was to diminish the chances of success, and that the best results were to be obtained by risking enormous casualties, extending the area of the battle , and limiting its possible duration in time.’²

Whether or not by then the authorities knew the truth of the following statement or were just trying to give the British people some good news, it continued, ‘But they have failed to accomplish their strategic hopes of breaking the British line over a wide area and of sundering our communication with the French. It was a game on a breakdown which, in spite of our heavy defeats, seems in fact not to have taken place.’²

The Casualties

Most poignantly, The Guardian also included the following, under the heading ‘The Fallen’:

‘It is not easy, even in this late day of the war, for the average person to translate into human terms what is meant by ‘withdrawal,’ ’evacuation,’ ‘taking up new positions to the west,’ and it is impossible for the stay-at-home person to know what heights of sacrifice, what strains of spirit and body have been endured, what appalling experiences are covered by the phrase ‘have distinguished themselves by the valour of the defence.’

But this Sunday most people were thinking of the deeds over there, and of the men who were giving their lives for their country. The toll in this the thickest fighting of the war was being paid in every minute of those quiet days of sun and mist. One thought often of the poems of young Robert Nichols³, written when fighting over this ground, especially the one which ends –

‘I pray you when the drum rolls let your mood

Be worthy of our deaths and your delight.’’²

13th (Service) Battalion War Diary – 25th March 1918 – No 1 Sector, Olasli

The Battalion in Open Warfare. 1 OR compulsorily transferred to the RE with effect from 14-1-18. 16 OR have been transferred to the Labour Corps with effect from various dates. 4 OR having rejoined are again taken on the effective strength with effect from 24-3-18. 4 OR (Draft) having joined are taken on effective strength from 25-3-18. Coy League matches.

References & Further Reading

¹ ‘Warfare 1917-1918 (USA)‘ by Mark E. Grotelueschen in International Encyclopedia of WWI

² Various Articles in ‘The Guardian’ newspaper on March 25th, 1918.

³ Robert Nichols (1893-1944), war poet, served in WWI from 1914-1916 when he was invalided with shell shock. These are the last two lines of his poem ‘By the Wood’, the previous lines read:

‘O youths to come shall drink air warm and bright,

Shall hear the bird cry in the sunny wood,

All my Young England fell today in fight:

That bird, that wood, was ransomed by our blood!’

He is one of the 16 Great War poets commemorated in Poet’s Corner in Westminster Abbey.

º ‘Second Battle of the Somme‘ in a HistoryofWar.org