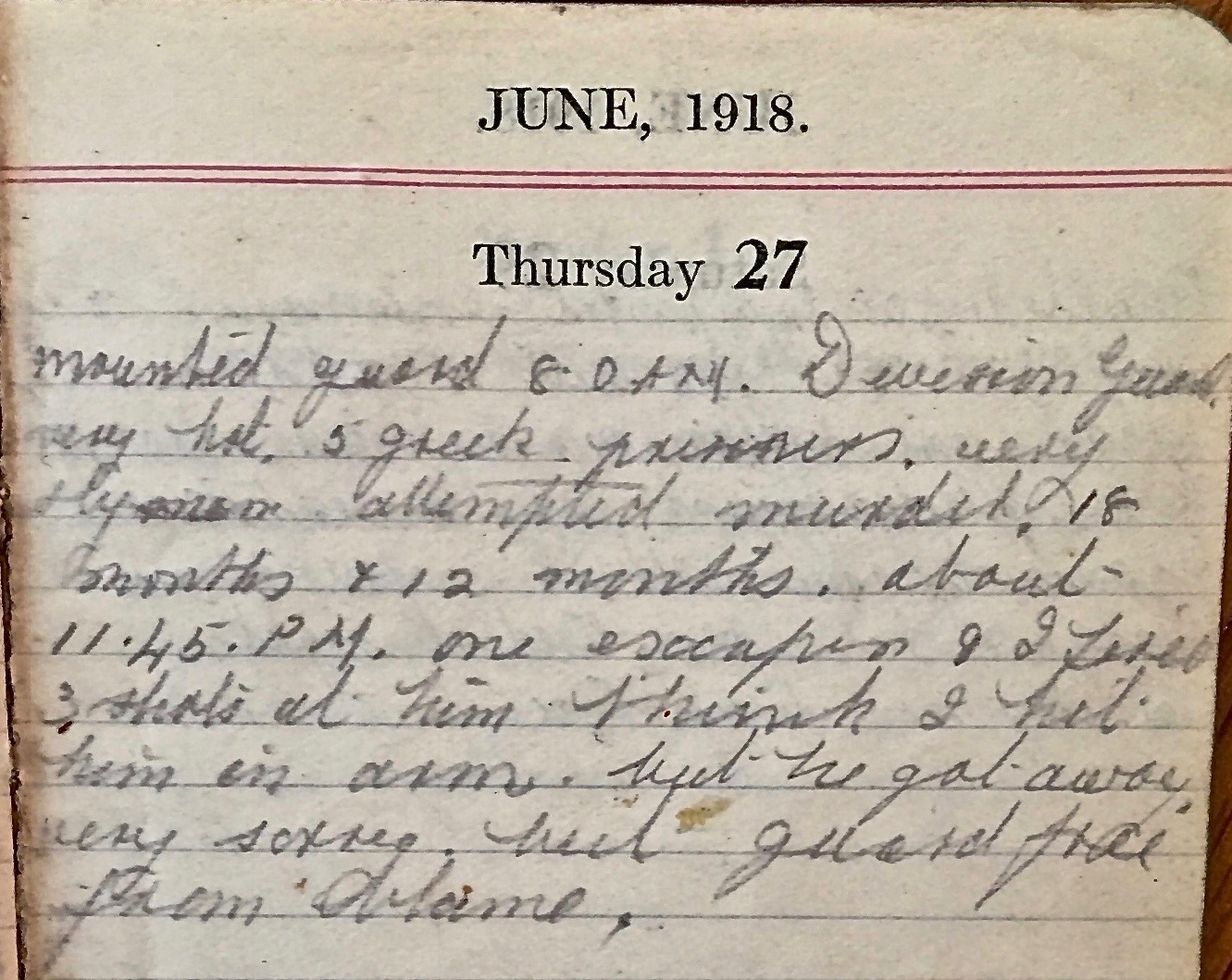

Thursday June 27th, 1918

Mounted guard 8am. Division Guard. Very hot. Five Greek prisoners. Very sly men – attempted murder – 18 months and 12 months. About 11:45pm one escaped and I fired three shots at him. I think I hit him in the arm but he got away. Very sorry but guard free from blame.

Prisoners

An escaped prisoner and shots fired – seems like quite a big deal to me – but there is nothing about it in the Battalion War Diary. It could be because Frank is actually mounting Divisional Guard today – presumably for the 22nd Division, of which the 13th is a part.

Military Justice

It would be interesting to know more about this case. The Greek prisoners could have been labourers working for the British Army – in which case they would fall under the its system of discipline. However if they were serving with the Greek Army, they presumably would have been tried under theirs.

Each country had its own law code. In Britain for example this was made up of the Army Act of 1881, the 1912 edition of the King’s Regulations and the 1914 Manual of Military Law.

Apparently all law codes were designed in anticipation of short wars and large battles. The sheer duration and nature of WWI apparently put significant strains on the mechanics of military discipline.¹ Regardless, justice wasn’t always the priority.

By the end of 1914, there were ~5,000 British soldiers in custody. Counter-productive to the war effort, this led to a re-think. From 1915, most punishments were commuted to ensure the culprit remained on active service.

The Prisoner

The prisoners, according to Frank, have been found guilty of attempted murder. Under the British Army, this would have been determined by court martial. According to the Manual of Military Law, attempted murder was ‘an offence punishable by ordinary law’:

‘An act which constitutes an offence if committed by a civilian is none the less an offence if committed by a soldier and a soldier not less than a civilian can be tried and punished for such an offence by the civil courts.

In order to give military courts complete jurisdiction over solidiers, those courts are authorized to try and punish soldiers for civil offences, namely, offences which, if committed in England are punishable by the law of England.

They are not allowed to try the most serious offences – treason, murder, manslaughter, treason-felony or rape – if those offences can, with reasonable convenience, be tried by a civil court.’²

However ‘reasonable convenience’ was defined as within 100 miles of a British Judge – and therefore excluded offences in foreign theatres of war.

The Guard

Ironically the escape of the prisoner in this instance could also have led to a court martial – this time of the delinquent guards. This was defined in Section 20 of ‘Offences in relation to Persons in Custody’ within The Army Act:

’20. Every person subject to military law who commits any of the following offences; that is to say,

1. When in command of a guard, picket, patrol, or post, releases without proper authority, whether wilfully or otherwise, any person committed to his charge; or

2. Wilfully or without reasonable excuse allows to escape any person who is committed to his charge, or whom it is his duty to keep or guard,

shall on conviction by court-martial be liable if he has acted wilfully to suffer penal servitude, or such less punishment as is in this Act mentioned, and in any case to suffer imprisonment or such less punishment as is in this Act mentioned.’²

Thank goodness, as Frank notes, the ‘guard free from blame’. Presumably shooting at, and possibly wounding, the prisoner was a redeeming feature!

13th (Service) Battalion War Diary – 27th June 1918 – Divisional Horse Show Ground, Cugunci

Fatigues and training as before. A CRO published on the prevention of Grass Fires.

References & Further Reading

¹ Military Justice in International Encyclopedia of WWI

² Manual of Military Law, War Office, 1914, (HMSO, London) reprint 1917 (pages 85 & 398)