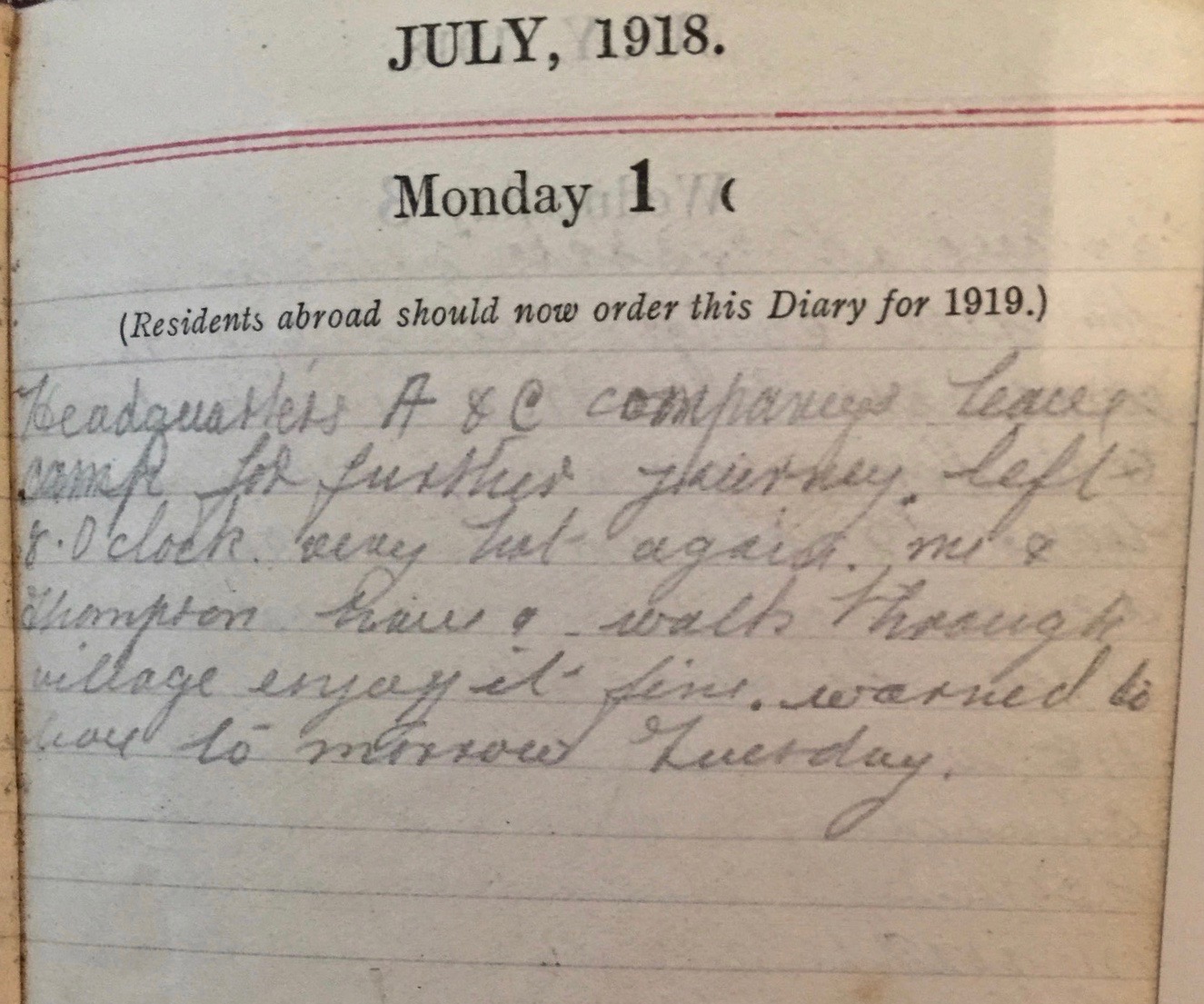

Monday July 1st 1918

Headquarters A & C companies leave for camp for further journey. Left at 8 o’clock. Very hot again. Me and Thomson have a walk through village, enjoy it fine. Warned to leave tomorrow, Tuesday.

Place Names

Today the BWD lists a number of places that the trains will stop at, en route to the Greek coast. However trying to track places mentioned in both Frank’s and the Battalion’s Diary has always proved difficult. This is partly due to language – obviously many original place names were written in Greek and therefore phonetic translations can result in many spellings.

It is also partly due to significance: in a sparsely populated land, naming every grassy knoll and crevasse is not required in peace time.

However, the Allies had to create a lingua franca for hundreds of thousands of personnel. All had to know where they camped, worked, attacked and defended. They also needed to know where to send supplies and reinforcements, as well as their wounded.

Consequently, the maps that were created by the Allies during WWI gave place names to every hill and valley – both on their side of the line and the enemy’s.

Whenever a prisoner of war was interrogated, finding out what the enemy called places was important intelligence. This is made clear in this extract from an interrogatory (Appendix 4) of the BWD in May 1918.

A Rose by Any Other Name

.Another problem with place names relates to the history of the region. This is described colourfully by J Johnson Abraham. He was a British doctor who travelled to Serbia in 1914 as part of the humanitarian effort.

‘On the day after our arrival, while our Chief, aided by the British Consul, was having solemn talks with the authorities over our future activities, we took the opportunity of wandering through the picturesque old city, which we were now told should be called Skoplje and not Uskub.

Nearly every town of any size in the Balkans, we found, had from two to five names, and it was not for some time after our arrival that we came to understand the hidden meaning of this multiplicity.

For the choice of name for any place in certain areas indicates at once the political views and nationality of the person using it. For instance the capital of Turkey in Europe to the Mussulman is Istamboul, to the Christian of the Balkans it is Tzaregrad (the city of Caesar), to the Greek and people of the west, Constantinople. Similarly, what is Monastir to the Turk is Bitolia to the Serb, and something else to the Bulgar. Our present habitat we came to call Skoplje or Uskub indifferently, although we knew that Skoplje was the ancient historical name of the city of Stefan the Strangler, and Uskub merely a Turkish corruption of the sound of it.’¹

The city described by Dr. Johnson Abraham had only become officially known as Skoplje when it was annexed by Serbia in 1912 after the Second Balkan War. After WWII it would become ‘Skopje’ when the region became the Socialist Republic of Macedonia within the newly created Yugoslavia.

Aftermath

Since the break up of Yugoslavia in 1991, the country has been known internationally as ‘the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia’. This is primarily because Greece objected to the country trying to call itself the Republic of Macedonia. It is now provisionally the ‘Republic of North Macedonia’ – following an historic agreement in June 2018 with Greece.³

13th (Service) Battalion War Diary – 1st July 1918 – Sarigueul

As detailed in Operation Order No 40 (Appendix III of June 1918), HQ, A & C Coys entrained at 08:30 hrs starting out at 09:30 hrs. Travelled via Dudular, Ekaterina and Larissa. At Ekaterina tea was provided free for all ranks by the YMCA while at Larissa the same tea was made.

References & Further Reading

¹ ‘My Balkan Log’ by J Johnson Abraham, London, Chapman & Hall, 1921, page 31

² Skopje on Wikipedia

³ Macedonian naming dispute on Wikipedia