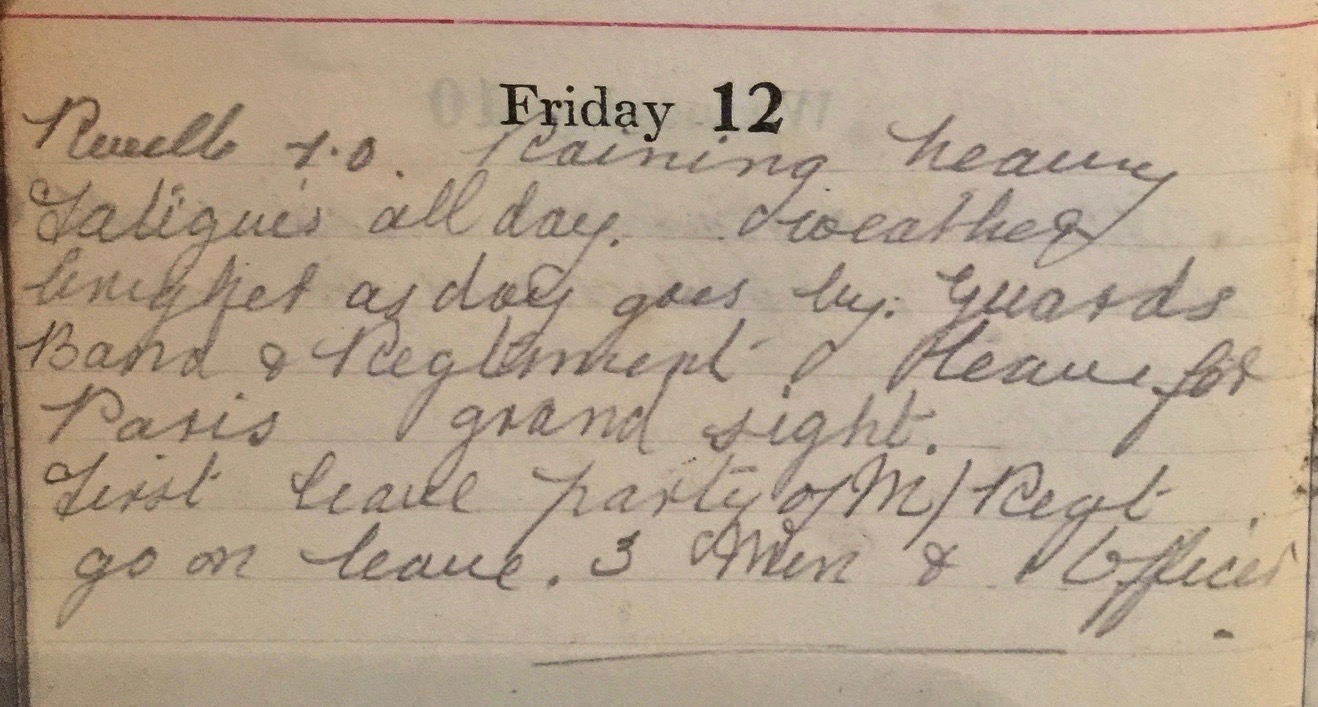

Friday July 12th, 1918

Reveille 7am. Raining heavily. Fatigues all day. Weather brighter as day goes by. Guards Band and Regiment leave for Paris – grand sight. First leave party of Manchester Regiment go on leave – three men and one officer.

Home Leave

Now that the 13th is in France, both Frank and the Battalion’s Diary seem excited about the new schedule of home leave for soldiers of all ranks.

In 1914, the war was expected to be brief and decisive. Therefore no provision was made for home leave for either officers or soldiers on either side in the conflict. This changed in 1915 – especially for those on the Western Front – though remained a contentious subject for all nations throughout the war.

As late as October 1918, Mr Macpherson, the Under Secretary for War, was forced to defend the record of home leave for soldiers to the House of Commons,

‘..improved leave arrangements are now in force. The average number of men coming home from France during September was 6,245 per day. The weekly leave party from Italy numbered 1,000. A regular leave service had also been established from Salonika. In the case of Palestine and Mesopotamia the position was more difficult owing to transport difficulties, but everything possible was being done, and he understood that, failing home leave, local leave to India or Egypt was freely granted.’†

Officers & Men

We have already seen evidence in Salonika that officers had some chance for home leave and could also be sent back to Blighty for training courses, sometimes for several months. This wasn’t the case for many of the Tommies who, like Illtyd Davies, might manage a few days off in Salonika town if they were lucky.

On the Western Front, the difference in treatment between officers and men was also striking. ‘In the British Army, for example, soldiers were allowed a leave every fifteen months on average, while officers were allowed one every three months.’¹

Theatres of War

Like the BSF, soldiers in Egypt and Mesopotamia and others, who were based in theatres of war that were remote from their home countries, fared the worst. Members of the Anzac forces could really only expect to get home if they were recuperating from injury or illness. Although interestingly in September 1917, the Guardian reported that 5,000 of the ‘original Australian soldiers’ would be going home for a holiday, ‘irrespective of whether reinforcements were sent as authorized’.²

Problems of Leave

Little consideration was given to the time it took a Tommy to get home from the Western Front. All soldiers seemed to get 15 days leave wherever they might live in Britain. The time it took and the ease of getting home could be compromised by many factors. Some were reported in the Guardian:

‘Everyone who has seen soldiers on leave struggling into train or bus with their enormous load of full equipment has asked the obvious question – “why can’t they leave their kits in France till they want them again?” …. The official reply … is to the effect that the soldier home from France must burden himself with sixty pounds weight of weapons and kit – in case of invasion. If some change could be made in this system it would be a great addition to the comfort of the soldiers, and would save a good deal of space in boat and train.

…. We have all seen soldiers at the London stations crowding round the pay boxes to change their French notes into English money. This takes so long that a soldier sometimes misses the only train of the day to his district and home. The average soldier coming home on leave receives a hundred francs. Why should he not receive his pay in English money on the other side?’³

Some charities tried to help out. One such was the ‘Stranded Soldiers’ Transport Service’. In a month this helped over 1,000 soldiers, stranded by late trains arriving in Manchester, to get to their homes.º

Ration Provisions on Leave

Once rationing was introduced in Britain in early 1918, feeding the soldiers became another dilemma:

‘Soldiers on leave will be given special journey tickets, which will enable them to purchase food at railway refreshment rooms and other places specially provided for the purpose.

The military authorities in France have been authorized to permit the returning soldier to purchase three tins (12oz each) of preserved meat from army stocks. On arrival the soldier will obtain a food card from the local food authorities on production of his furlough form.’ª

13th (Service) Battalion War Diary – 12th July 1918 – Abancourt, France

Day showery. Domestic fatigues. Major RML Scott MC, 2nd in command departed on leave (14 days) together with 3 OR, C Coy. Allotment of leave to England granted to the Battalion is 4 per diem, all ranks. For purposes of leave the Battalion has been divided into five – four companies and Headquarters each sending a party in train. All ranks started taking quinine 15 grains per diem.

References & Further Reading

† Article ‘Soldiers’ Leave’ in The Guardian, October 17th, 1918, page 6

¹ ‘Soldiers on Leave‘, 1914-1918 encyclopedia

² The Guardian, September 15th, 1917, page 7

³ ‘The Soldier’s Kit and Purse on Leave’ in The Guardian, November 26th, 1917, page 4

º ‘Stranded Home Coming Soldiers’ in The Guardian, February 26th, 1918, page 3

ª ‘Food for Soldiers on Leave’ in The Guardian, February 16th, 1918, page 7

* Q 30505 , copyright Imperial War Museums

** Q 30515, copyright Imperial War Museums