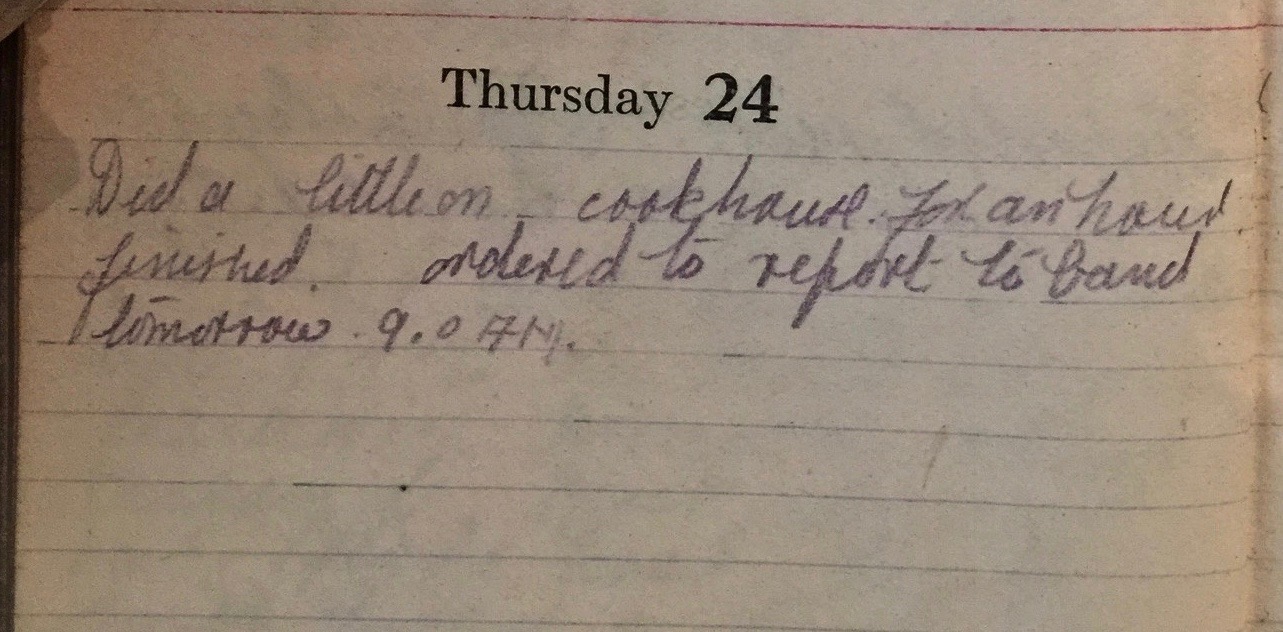

Thursday October 24th, 1918

Did a little on cookhouse for an hour. Finished. Ordered to report to band tomorrow at 9am.

Back with the Battalion Band

After practicing with them for the past couple of days, Frank has been ‘ordered to report to the Band tomorrow‘.

What this might mean in practice, I don’t really know. From earlier War Diary entries, we know that they had a training program distinct from other groups within the battalion. And there seems some debate about whether band members were expected to fight as part of the battalion.

I haven’t been able to find much about how Bands operated during WWI and what I have found is rather inconsistent. This could be because they existed at various levels within the British Army, including Regimental and Battalion Bands.

Band Members as Stretcher Bearers

Some claim that Band members were not expected to fight. For example, Major Travis Hampson, a doctor with the RAMC, wrote:

‘These regimental stretcher bearers are not RAMC, but the bandsmen of the regiments, who have been given some instruction in first aid and stretcher bearing, the band instruments all being left at home.’º

This is backed up by personal accounts, such as that of Charles Pickworth, who was a member of the band of the first Bradford Pals (16th West Yorks). His entry for July 1st 1916 read:

“The enemy shelled us with tear gas. The band lost two men and a few shell-shocked. At this stage the wounded had to be fetched in. Our front line filled up with dead and wounded. It was a terrible job. We worked day and night under heavy fire from their artillery and the snipers were very busy. The shelling continued but both sides were busy with wounded and dead.”¹

On July 6th, the remnants of the band played as the survivors came back from the line.

To Fight or Not to Fight

In contrast, on March 27th, 1918 at the Battle of Rosieres, in the first, frantic days of Germany’s Spring Offensive:

‘During the afternoon Brigadier-General Grogan, with two battalions and a number of details, including the Pipe Band, Drums, Tailors, Shoemakers and Storemen of the Battalion made a most successful counter-attack and re-took Harbonnieres and Vauvillers.’²

For this action, Grogan was awarded a Bar to his DSO. His citation read:

‘For conspicuous gallantry and devotion during a long period of active operations. On one occasion, when in command of the left division, it was mainly due to his personal efforts that the line was maintained and extended when troops of the left were withdrawn. Whenever the position became critical he went forward himself to restore the situation, and his splendid example of courage and endurance greatly inspired all ranks.’ ³

There is no record of whether the tailors, shoemakers or band members received any accolade. However, Brigadier-General Grogan must have been quite a hero. Just two months later, at the Third Battle of the Aisne, he would receive the Victoria Cross.†

9th Battalion War Diary – 24th October 1918 – Elincourt

Companies were inspected by the Commanding Officer, after which Coys carried out a route march. Lewis Gun training commenced under 2/Lt PHH Davies at HQ. Reinforcements were divided amongst Coys as under: in A Coy 25 OR, B Coy 40 OR, C Coy 26 OR and D Coy 58 OR.

References & Further Reading

º ‘1914 to 1919, A Medical Officer’s Diary and Narrative of the First World War’ by Travis Hampson MC, edited by Travis Philip Davies over the period 1999-2001

¹ ‘Instrumental role of military bands in WWI‘ by Claire Armstrong in The Telegraph and Argus newspaper

² ‘The Diehards on the Western Front (Volume 2)’ by Everard Wyrall (Middlesex Regiment)

³ Page 2609, Edinburgh Gazette, July 29th, 1918

† Page 8723, London Gazette, July 23rd, 1918

* Image from Wikipedia is believed to be in the public domain