The Temperance movement had been in existence for almost a hundred years at the outbreak of war. Originally, as the name suggests, the movement urged temperate alcohol consumption. Over time its philosophy had evolved to one that petitioned for prohibition. The Salvation Army, to which Frank and his family belonged, were prohibitionist. Founded by William and Catherine Booth in 1865 in London’s East End to help the desperately poor through ‘soup, soap and salvation’ , the Army had abstinence at its heart.

One of the sayings that has come down the generations of the Whitehead family (now used more in jest) is ‘Lips that touch liquor shall never touch mine’. This is from an old Temperance song:

Drunkeness interferes with the War Effort

However it wasn’t only the Temperance movement which thought that Britain had a drink problem. There were 42 million in England, Scotland and Wales before the outbreak of war. Yet Britain produced and consumed 36 million barrels of beer (each holding 288 pints) a year.² This equated to almost 31 gallons of beer per capita, plus spirits.

In Britain and Germany, beer was the national drink and in France and Italy it was wine. In these countries, the national drinks were identified as food stuffs, and by default, therefore, not luxuries. This is important because, as the war progressed, there was increasing pressure on the public to refrain from luxuries.

The Government was concerned that drunkenness would have an impact on Britain’s ability to wage the war and its industrial output. It was especially worried about dangerous work environments, such as munitions factories. Lloyd George, variously as Chancellor of the Exchequer, Minister of Munitions and Secretary of State for War between 1914 and 1916 when he became Prime Minister, was very concerned about the impact of ‘demon drink’ , but he was also a pragmatist. So the focus of the Government efforts was more on industrial efficiency and the war’s outcome than morality.

For the Duration

Temperance societies started to echo this sentiment by encouraging people to sign ‘pledge cards’ for ‘the duration’. Even King George V in April 1915, declared that no wine, spirit or beer would be consumed in His Majesty’s houses until the war’s end. The Defence of the Realm Act (1914), amongst many other provisions, restricted the opening hours of public houses for the first time (five and a half hours split between lunch time and early evening³). Various other measures followed, including the introduction of a minimum legal drinking age and banning alcohol on trains . They even outlawed ‘treating’ (ie buying drinks for someone else or buying drinks on credit). Excise duty was also increased (by 1918 a bottle of whisky was five times the price it had been in 1914) and alcohol content was reduced.

In May 1915, the Central Control Board (CCB) was given the right to take control over breweries and public houses in naval, military, munitions and transportation areas. The following year, the CCB took over five breweries and 363 licensed premises around Carlisle, other parts of Cumberland and the south west of Scotland which surrounded a large munitions site in Gretna that employed 15,000 people. The restrictions remained in place in Carlisle until the late 1960s.º

The authorities’ efforts had a significant impact. By 1916, beer production had fallen to 26 million barrels and the target for 1917 was 18 million with a stretch of 10 million.

One last push

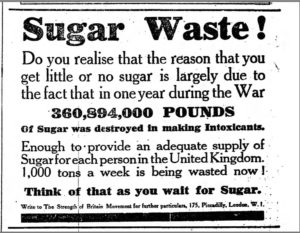

In late 1917 and 1918, when food shortages were pronounced and rationing was being introduced on staples such as sugar, the Temperance movement once again tried to latch onto public sentiment to progress their agenda with adverts like this, which appeared in The Manchester Guardian on January 1st 1918.¹

On February 6th, 1918, The Times reported a question in the House of Commons by a Member of Parliament for Lanarkshire, Scotland, a region with a strong temperance movement. Mr Duncan Millar asked what amount of ship tonnage (another scarce item by then because of U-boat activity) would be freed up if the output of beer was reduced to ’10% of the pre-war standard, as in Germany, to 6%, as in Austria, or if the further manufacture of beer and spirit was prohibited’. In the answer, the potential saving ranged up to 575,000 tons which was the equivalent of ’29 ships, each of 5,000 tons cargo capacity, making four voyages a year’. Despite being discussed in the War Cabinet, balancing supply with demand was recognized to be a delicate act and the Government were keen not to encourage the replacement of beer with spirits.

After the War – in Britain & the USA

Drinking in Britain never returned to pre-war levels. By the 1930s beer consumption was 13 gallons per capita, down by 58% since the outbreak of war.‡ Several of the provisions of the war-time legislation, although changed in detail, remain in place to this day. However the Temperance movement wained.

By contrast, in the USA, a motion was debated in the Senate in 1918 to make the nation entirely dry from July 1st 1919 until the troops were demobilized.† This foreshadowed the 18th Amendment to the Constitution and the Volstead Act, and from 1920, prohibition was introduced across the country.

References & further reading:

‘Lips that touch liquor…’ sung by the Women’s Choir at Concordia College in February of 2016 for inclusion as part of the exhibit “Wet and Dry” at the Historical and Cultural Society of Clay County. Photos in the video came from the collections. The video was created by NDSU Public History Student Luke Koran.

º The Carlisle Experiment – limiting alchohol in wartime by Roger Kershaw in National Archives

¹ Clipping from Manchester Guardian, January 1st, 1918, Copyright © 2017 Newspapers.com.

² The Manchester Guardian (24th January 1917 reporting Lloyd George’s speech to Parliament)

³ ‘Gender, Class and Public Drinking in Britain During the First World War’ by David W Gutzke

† Report in The Manchester Guardian, November 22nd, 1918

‡ ‘A report by the Brewer History Society for English Heritage’ February 2010. Text by Lynn Pearson

‘The Enemy Within – the battle over alcohol in WWI‘ in The Conversation