Frank records the number of letters he writes to his wife, family and friends in his diary, and delights in those he receives. He clearly gets anxious if he hasn’t had a letter for a few days and is ecstatic when he receives a paper from home full of local news. His reactions were not unique. With millions of soldiers abroad, there was a huge and insatiable two-way demand for postcards, letters and newsprint. By December 1917, 25 tons of outbound mail to the armed forces was being handled every day. This translated to over 12 million letters and newspapers each week, two thirds of these to the troops in France. Volumes more than doubled in the run up to each Christmas. All these numbers exclude parcels, which peaked at a million in the month of April 1917 before declining significantly as shortages became more acute on the home front.¹

The Post Office before the War

Before the war, Britain’s Post Office was the biggest employer in the world with over 250,000 employees. With annual revenues of £32 million, it was also the largest economic enterprise in the country. The Post Office was responsible for the collection, sorting and delivery of almost six billion postal items annually. It had introduced the penny post as a uniform rate for letters in 1840 with the famous Penny Black stamp, and would maintain this rate unchanged until July 1918. In 1913, even small towns could expect up to 12 postal deliveries a day. With postcards at a half penny each, messages could be exchanged between well-organized parties several times in a day. The Post Office was also responsible for both the telegraph and telephone services and a savings bank.²

During the War

Despite the scale and scope of the Post Office, the infrastructure and effort required to handle the international war-related demands were immense. These challenges were compounded by staff shortages. By Christmas 1914, the Post Office had lost over 10% of its workforce to the armed services, including 12,000 to the Post Office Rifles which was to see heavy fighting in Ypres and the Somme. Over the course of the war, it would lose a total of 75,000 employees to the war effort. Their places were assumed by thousands of women and other temporary employees taken on ‘for the duration’.

Until late 1917, when regional depots were utilized, all mail destined for the armed forces was routed through the Home Postal Depot in London for sorting and despatch. The primary depot was a huge, wooden, purpose-built structure set on five acres of Regent’s Park.

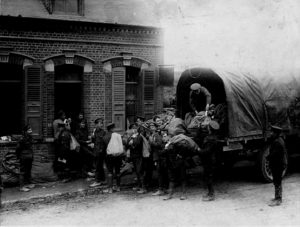

Once processed, the mail was then sent on to Base Army Post Offices (BAPO) that existed in every theatre of war. From there it was distributed to the Field Post Offices, mobile units that were close to the front. Unit Postal Orderlies collected the mail from there and delivered it to the troops.

The Army Postal Service ran the Base Army and Field Post Offices. By the end of the war, it had over 7,000 men and women serving in it, all of whom were seconded from the General Post Office.³ The service worked very well. A special correspondent for The Times reported on December 22nd 1917 that parcels arriving at the BAPO in France on the 18th had left Belfast on 13th and Glasgow on 14th; and that letters were taking less than 48 hours from Aberdeen and Wolverhampton.

Creaking at the Seams

However, when asked whether it was possible to reduce the cost of mail to overseas troops in December 1917, the Postmaster General responded: ‘The amount of transport required both in the UK, by sea and in the field to the regular and rapid delivery of this volume of correspondence is so considerable that I can hold out no hope of any concession which would increase the bulk of mail transmitted to the troops.’º In other words, the system was strained to its limits.

In summer 1918, the uniform penny post, in existence for almost 80 years, was abandoned and the rate increased by a half penny. Soldiers with the BEF still sent their mail home for free and all mail to servicemen continued to be charged at a penny.

Colonial Mail

Mail losses to enemy action, particularly at sea, were a constant concern. Despite this, mail for colonial troops was always routed through London for despatch.

On January 29th, 1918, The Times reported the visit of the High Commissioner for Australia to the Australian Base Post Office which had recently been set up in an old brewery on the Kings Road in London. All the Australian Expeditionary Force mail passed through this facility. In a three month period it handled 2.2 million letters and 50,000 parcels. Changes of location were tracked using a card index system. As a result, 97% of all mail was delivered successfully. For any parcel not delivered because the intended recipient had been killed – the Base Post Office arranged for articles of sentimental value to be returned to the sender. Other content was forwarded to the Australian Comforts Fund Commissioner for redistribution to other men of the Australian Forces.

Postal Censorship

On 6th December l917, the Queen and Princess Mary visited the Postal Censorship Department. The department was 4,200 strong – almost three quarters of whom were women. It censored 375,000 letters each day. About a third of these were commercial letters, largely destined for neutral countries all over the world, and the remainder private correspondence. The team also examined 120,000 newspaper packets and parcels daily. As a result, the Department helped to foil spies, uncover enemy-related trade deals and preserve military secrets. It also helped intercept tens of millions of pounds worth of remittances destined for the enemy.‡

During the war, the Post Office was responsible for the distribution of up to £2 million a week in ‘separation allowances’ paid by the Government to troops’ dependants. It also handled the mass, national distribution of various items, including ration books in early 1918. Needless to say, the more traditional domestic services suffered.

Post-War

The luxury of almost hourly mail services and the penny post disappeared forever. The Post Office laid off the majority of its temporary women workers. It also reintroduced its policy of not employing married women unless as sub-post mistresses. This policy was again suspended at the beginning of WWII and only abandoned for good shortly after it ended.

References & further reading

¹ Article in The Times, December 22nd 1917

² Articles on Postal History on Post Office Museum website

³ Article on the British Army Postal Service, Wikipedia

º ‘No cheaper postal rates for troops abroad’, page 10, The Times, December 7th, 1917

‡ ‘Work of the Postal Censors’, page 5, The Times, December 7th, 1917

* Photographs from the Post Office Museum website (images may be subject to copyright)

^ Photograph from collection of Field Marshall (Earl) Haig in the National Library of Scotland

Article on the history of the Post Office from The Telegraph