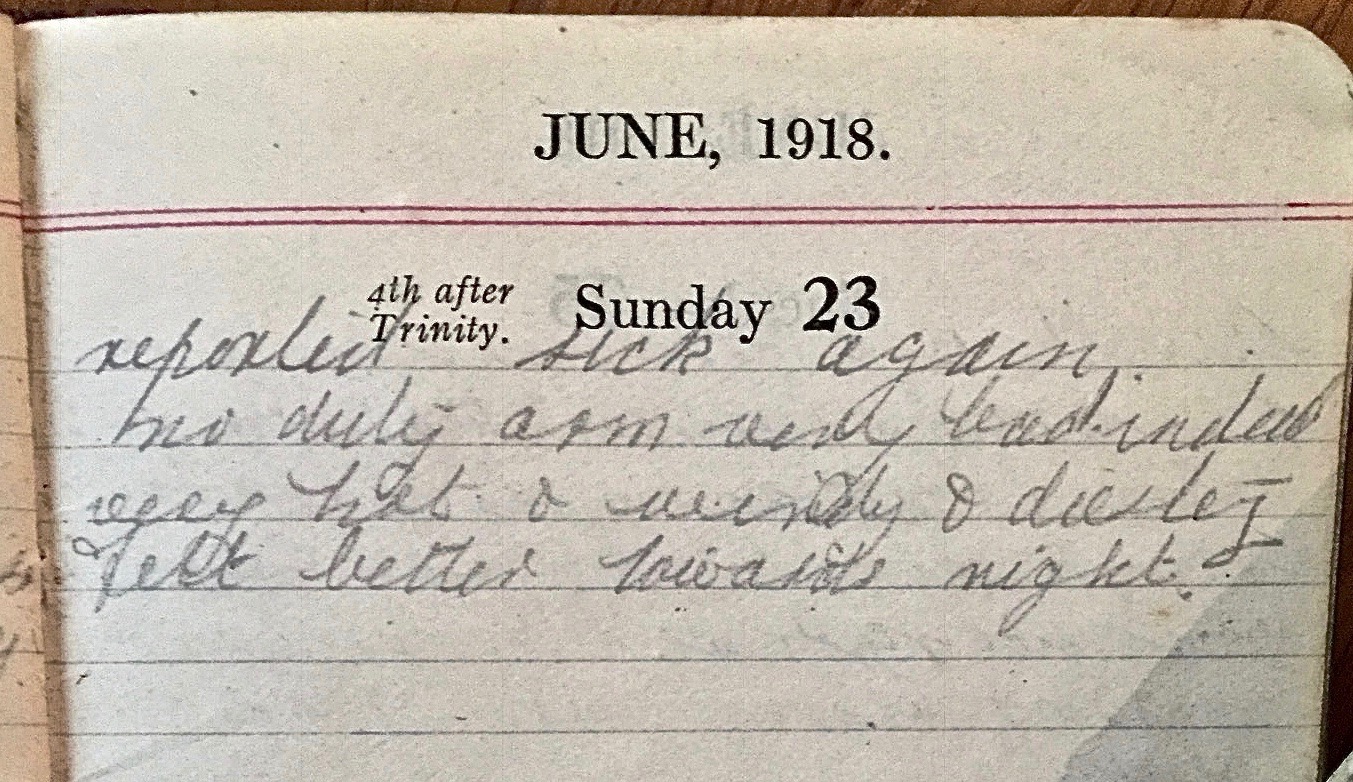

Sunday June 23rd, 1918

Reported sick again. No duty. Arm very bad indeed. Very hot and windy and dirty. Felt better towards night.

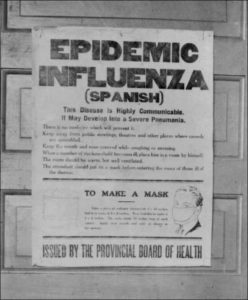

Spanish Flu

Frank is not well again today and has reported sick. Meanwhile back at home, Lancashire and many other parts of the UK are fighting Spanish Flu.

The epidemic began in spring 1918 and will peter out in summer 1919. Through this period, it will come in waves. The second wave in autumn 1918 will be the most virulent with deaths peaking in October and November. Around 500 million people will catch flu worldwide and the death rate will be between 5 and 20%. Unlike many other infections, the highest mortality rate is amongst young, fit adults. In just a year, it will cause the average life expectancy in the US to decrease by 12 years.²

The epidemic was possibly called the ‘Spanish Flu’ because its impact on Spain had been widely reported both domestically and internationally. This was in contrast to the reporting by the belligerent nations where, to safeguard public morale, all faced censorship about conditions at home.¹ That said the British newspapers were full of British flu-related news all summer.

A case in point was the reporting in late June and July in the Guardian. As the Manchester Guardian, it focused upon Lancashire. Initially the epidemic seemed contained within certain areas – predominantly Rochdale and the Rossendale Valley – however it rapidly spread. Despite starting with school children, a local doctor was quoted as saying, ‘From investigation, I think it will be much more difficult for adults to get over an attack than for children.’³

Within two days of this initial report, there were local deaths and the overall incidence rate and geographic spread increased rapidly. Before the end of June, the Manchester tram, telegraph and telephone services were impacted by staff shortages.

More broadly temporary hospitals were established in the harder hit communities such as Northampton and by July 2nd, employers estimated that 5 to 15% of the working population of London was impacted.³

One sign of censorship might be that reports of flu on the Western Front concentrated very much upon enemy sufferers. Indeed there were rumours that the timing of the later waves of the Spring Offensive were impacted by it.

Route Home

Lt Wallwork left the Battalion at the end of May to go to Machine Gun School back in the UK. U-boat activity in the Mediterranean had made the sea route unpopular. Instead the Lieutenant is taking the overland route by train, only crossing from Itea in Greece to southern Italy by boat. This will be the route followed by the 13th.

13th (Service) Battalion War Diary – 23rd June 1918 – Divisional Horse Show Ground, Cugunci

Sunday. Voluntary Services. Extract from London Gazette no 30686 dated 17-5-18 T2Lt JW Webb appointed Flying Officer (Observer) and to be transferred to the RFC General List 23rd March 1918 with seniority from 7th January 1918. Lt HB Neal embarked Itea 11/3/18 proceeding UK in accordance with WOL 100 / Machine Guns/1861(SP4). Lt W Wallwork embarked Itea 7/6/18 proceeding to UK in accordance with WOL 100 / MGC/OPG/SP4/1909.

References & Further Reading

¹ Spanish Flu on Wikpedia

² Spanish Flu on History.com

³ Various articles in the Guardian – May 1918 – July 1918. Quote from June 22nd, 1918, page 4

* Spanish Flu poster & info from the British Society for Immunology. Image (possibly Canadian) may be subject to copyright.